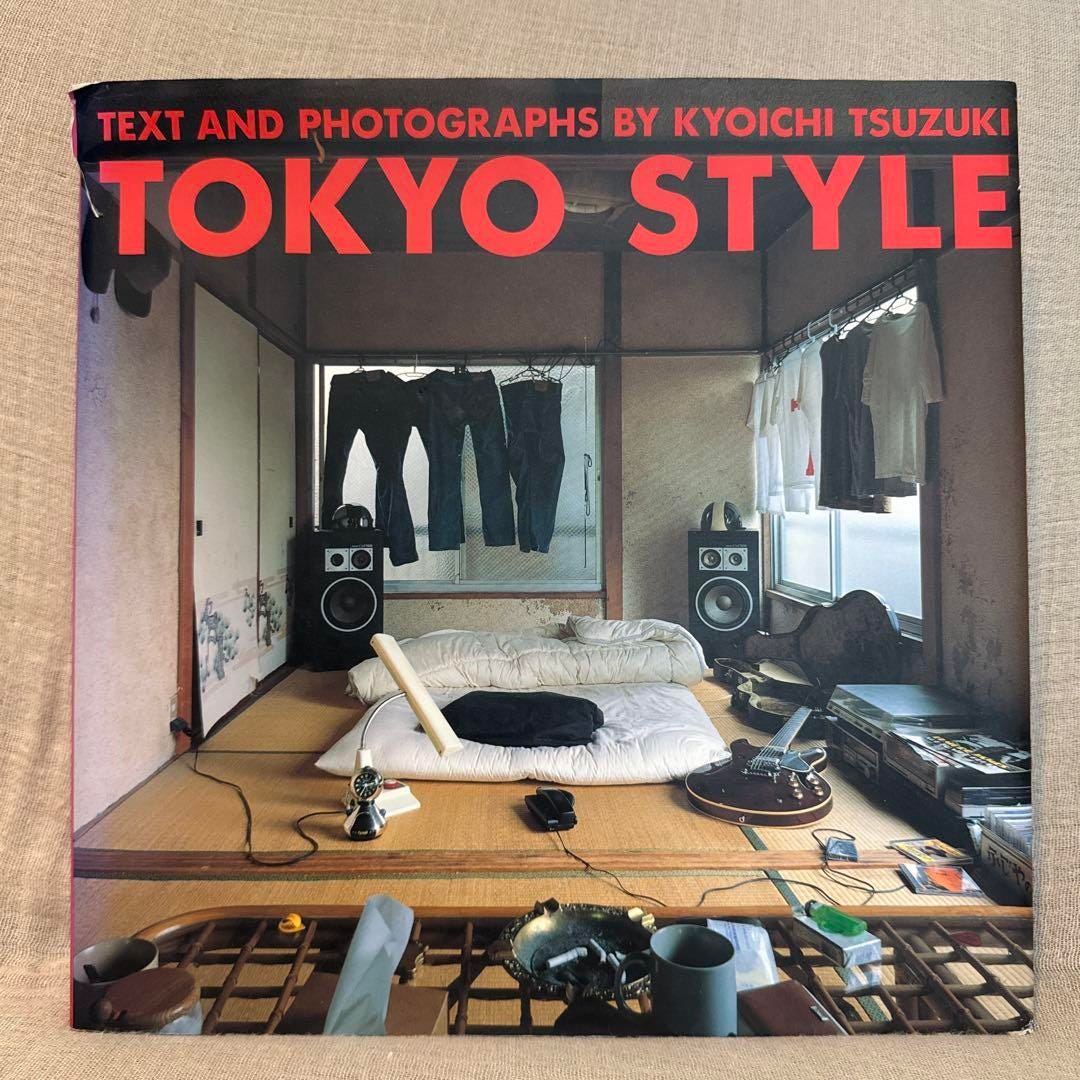

Japan’s Legendary Photo Book "Tokyo Style" Still Inspires After 30 Years

Japanese pop culture news edited by Patrick Macias

Photographer and editor Kyoichi Tsuzuki reflects on finding beauty in “ordinary life”

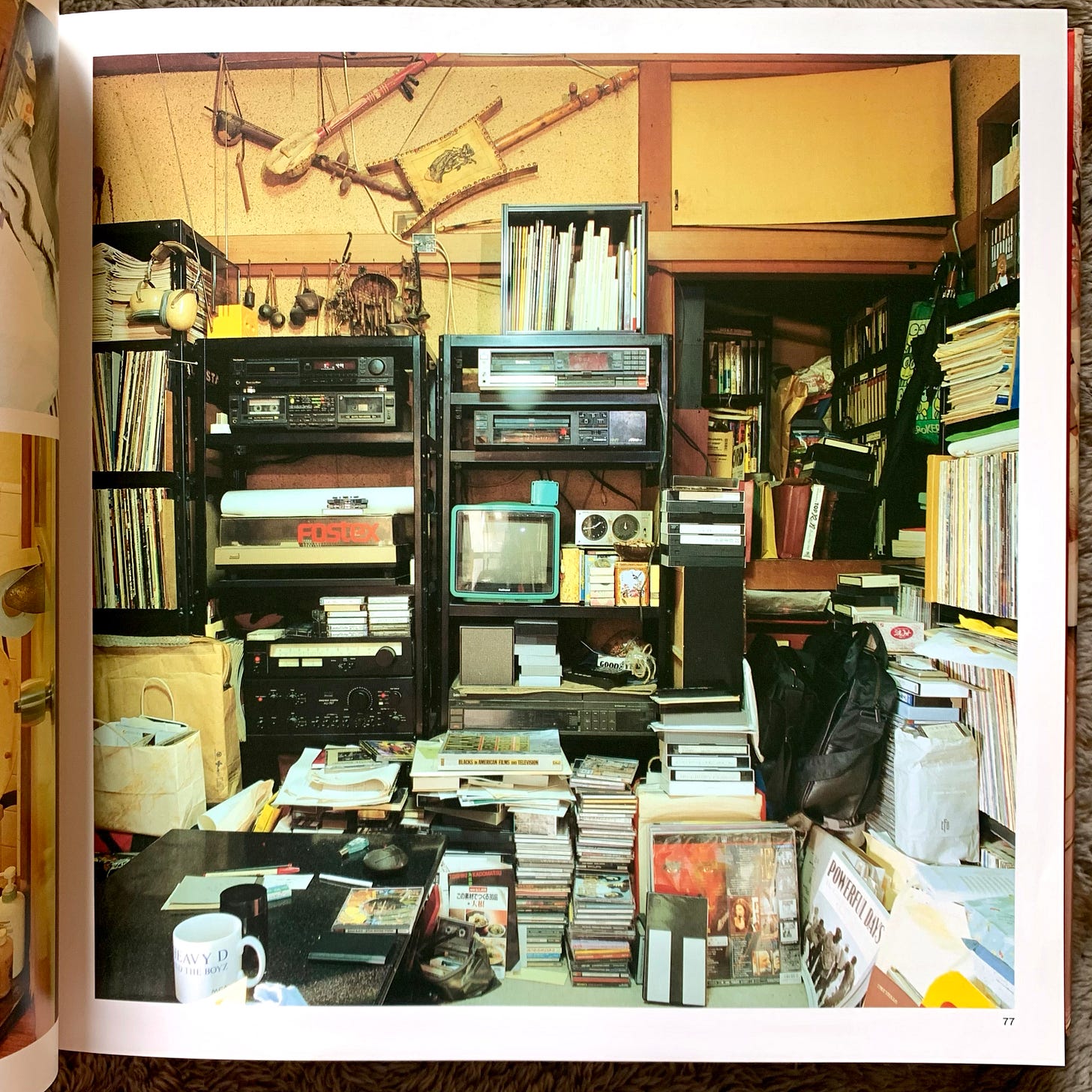

His 1993 photo book Tokyo Style captured real Tokyo apartments in all their cluttered glory

A new English edition from Spain’s Apartamento renews global interest in this rare look at everyday Japan

A Record of Ordinary Life That Became a Legend

More than 30 years after its first publication, Tokyo Style remains one of Japan’s most beloved and discussed photography books. Created by writer and editor Kyoichi Tsuzuki, the book captured “ordinary people’s ordinary rooms” in 1980s Tokyo: tiny apartments filled with laundry, futons on the floor, and personal chaos that felt alive. Recently reissued in English by Barcelona’s Apartamento in 2024, Tokyo Style continues to inspire photographers, designers, and readers worldwide.

Journalist Tomoko Hachiya, author of the essay collection Therefore, I Live Alone, described Tokyo Style as her “starting point.” “When I began my own series about solo living in 2024, Tsuzuki’s book was my model,” she said. “There’s a warmth and honesty in those rooms that today’s social media feeds lack. Every photo in Tokyo Style breathes with human temperature.”

When “Cool” Was Hard to Find

Kyoichi Tsuzuki came of age in the 1980s, when magazines like POPEYE and BRUTUS defined Japan’s youth lifestyle cultures. “Back then, every issue showed readers the ‘correct’ way to be stylish,” Tsuzuki recalled. “I worked on those magazines, so I was part of that system, but when we actually looked for people living those perfect lifestyles, we could barely find any.”

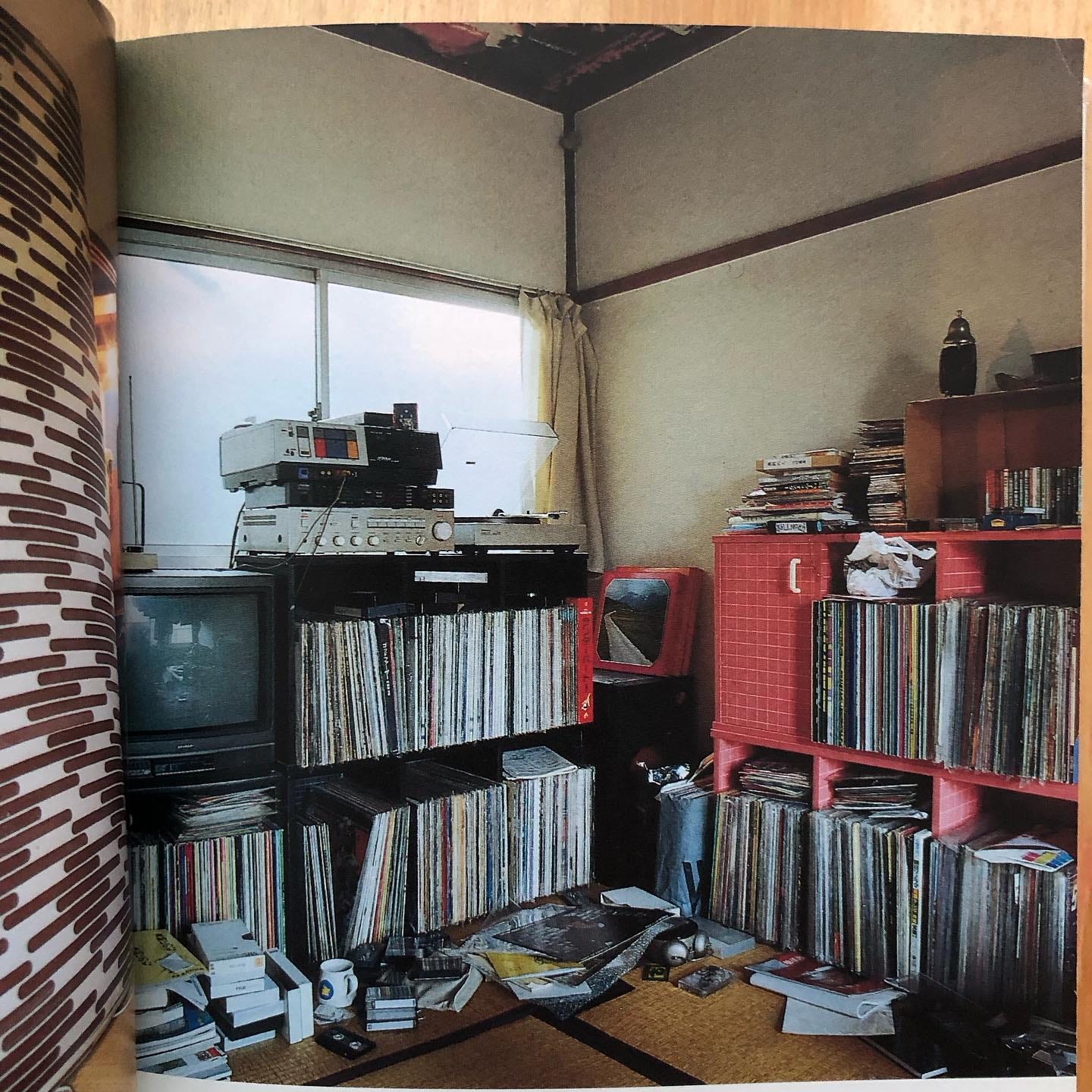

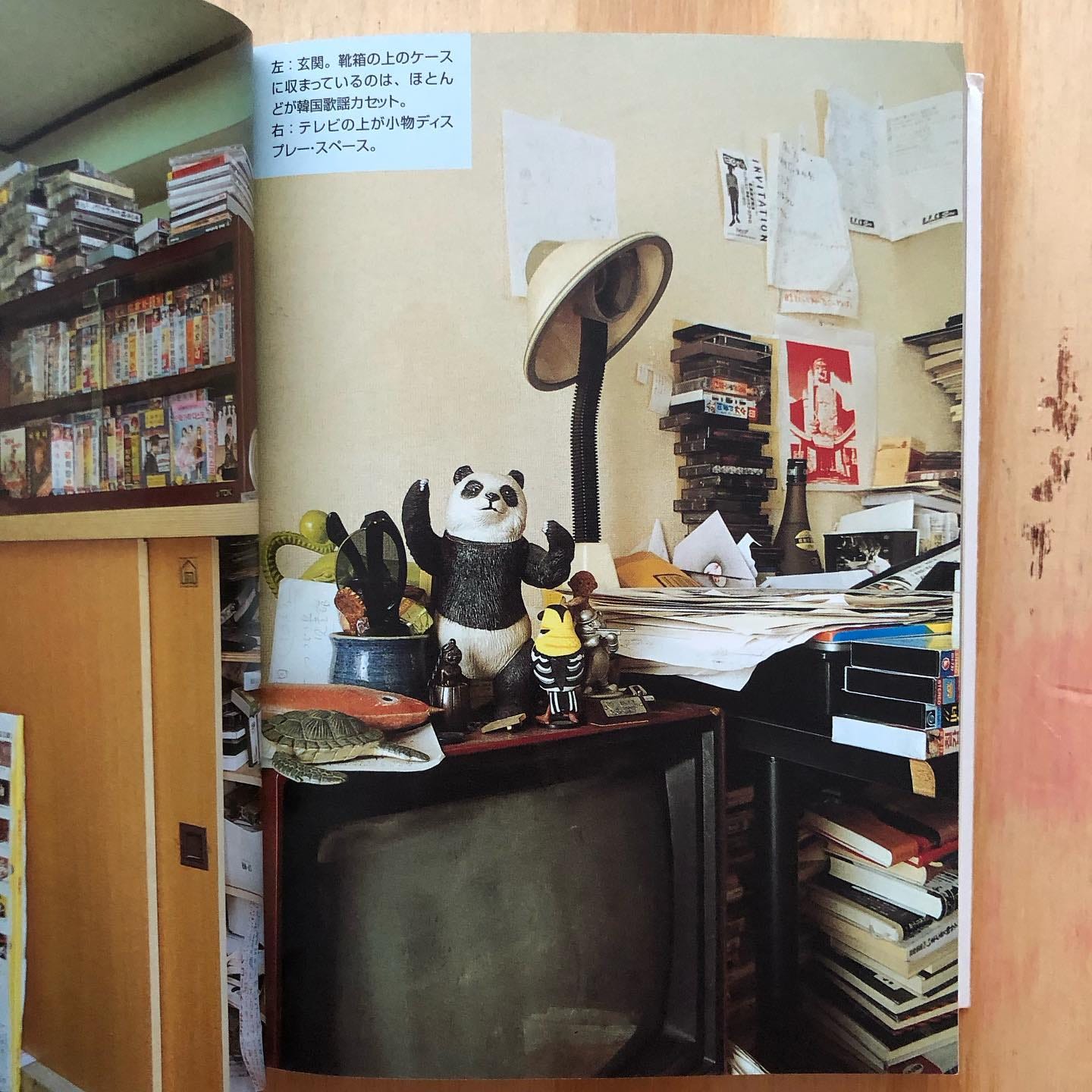

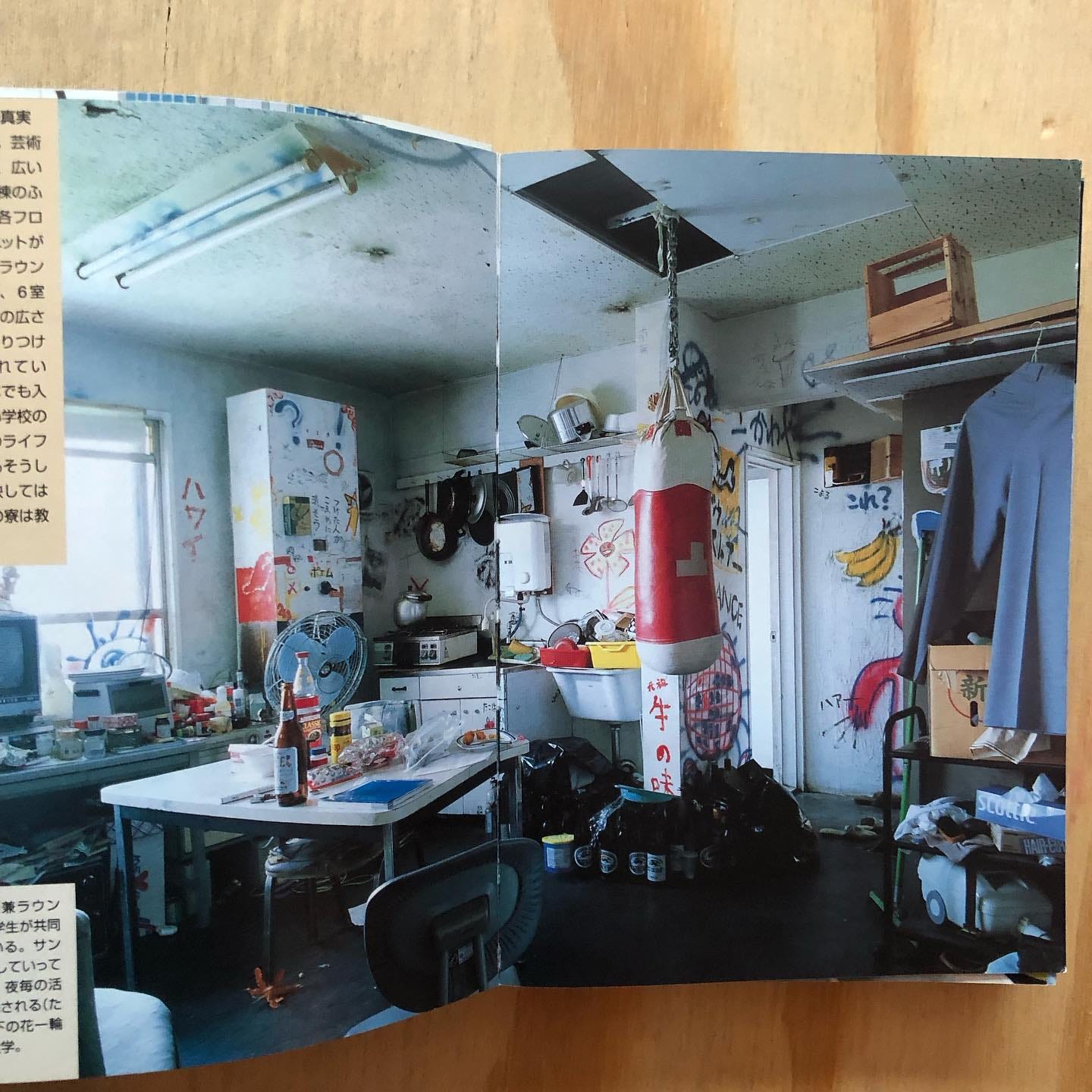

Most of his friends lived in small, messy rooms, far from the polished ideal on magazine covers. “We’d drink at someone’s cramped apartment with futons still on the floor, and it felt warm and real,” he said. “I realized if I photographed a hundred of these rooms instead of just a few, it might reveal something more interesting.”

Capturing “Uncool” Rooms With Respect

Instead of treating the clutter as a joke, Tsuzuki shot each apartment head-on, as if for an architectural magazine. “I didn’t want to mock them or make them look pitiful,” he said. “I wanted to document how people actually lived in Tokyo at that time.” The result was Tokyo Style, published in 1993, a collection of more than 100 rooms photographed across the city.

At first, publishers were skeptical. “No one wanted to touch it,” Tsuzuki said. “They told me, ‘Who would want to see messy rooms like this? They’re not pretty, they’re not inspiring.’ So I bought a camera myself, spent two or three years shooting, and forced a publisher to release it. That’s how Tokyo Style came to be.”

A Mirror of the World’s Small Spaces

After publication, the book struck a chord in Japan and abroad. “People from all over wrote to say, ‘This looks just like my home,’” Tsuzuki recalled. “The lives of young people in cities aren’t so different anywhere. That’s why it resonated globally.”

Since Tokyo Style, Tsuzuki has published over 30 books and produced exhibitions and projects celebrating overlooked parts of Japanese culture, from snack bars and enka singers to outsider artists. Now 69, he continues to publish his weekly newsletter ROADSIDEERS’ Weekly, keeping the same curious eye that made him famous.

Finding “Ordinary” in the 2020s

Hachiya, reflecting on her own work three decades later, said the world has changed dramatically. “Today, people show their lives online with calculation. Their rooms are cleaner, more curated. The clutter is gone,” she said. Yet even in neat apartments, she still sees traces of humanity. “In every photo, there’s a warmth; a kitchen, a bookshelf, a corner by the bedthat tells a story.”

Tsuzuki himself described Tokyo Style as “a record of life just before social media existed.” He added, “For younger people now, it might look nostalgic or even enviable.”

For Hachiya, the lesson is clear: “In an age where everyone performs for an audience, there’s meaning in documenting imperfection. Capturing real, unfiltered life is still powerful.”