INTERVIEW: Wild Style! Inside Japan's Heisei Retro Trend with Bisuko Ezaki!

The Menherachan artist talks about his favorite fashion, characters, music and more from the 1990s-2000s

Bisuko Ezaki is a Japanese artist best known for his original manga creation known as “Menherachan”, who reached a global audience in 2018 via a Refinery29 YouTube video called “The Dark Side of Harajuku Style You Haven't Seen Yet”.

Since then, Bisuko has dived headfirst into the growing “Heisei Retro trend” in Japan, and has been looking back for inspiration at the colorful styles and extreme youth cultures active in Tokyo from the 1990s to the 2000s (i.e., Japan’s Heisei Era).

In addition to sometimes dressing as a Heisei-era Gyaru-o (male gyaru), Bisuko has started chronicling his retro obsessions and activities on Twitter.

It seemed like a good time to check in and ask him about what Japanese youth culture was like then, and the challenges it faces now.

TokyoScope: I noticed recently that you’ve been posting a lot of images from Japan in the 1990s and during Heisei era on your Instagram and Twitter accounts recently, such as retro goods, pages from old magazines, and even posing yourself in retro fashion. Can you explain your current interest in this time period?

Bisuko Ezaki: In Japan, when the era changed from the Heisei era (1989 – 2019) to the Reiwa era (2019 – present), the term "Heisei Retro" emerged as a new concept. At the end of the Heisei era, there was a renewed focus on Japanese trends and culture from the 1990s to the 2000s, which helped create a new nostalgic trend. Now, with the Y2K boom, this older era continues to capture people's attention.

Recently, there have been many events such as revivals of old manga and anime, the release of new merchandise for classic characters, and café events. This has led many people in their late 20s and 30s, including myself, to once again indulge in the things we loved when we were teenagers.

Of course, I enjoy these things simply because they are nostalgic. But you could also say, 'we haven’t changed at all since the Heisei era.'

Why do you think Japanese youth culture was so strong and unique during the Heisei era? What made it special?

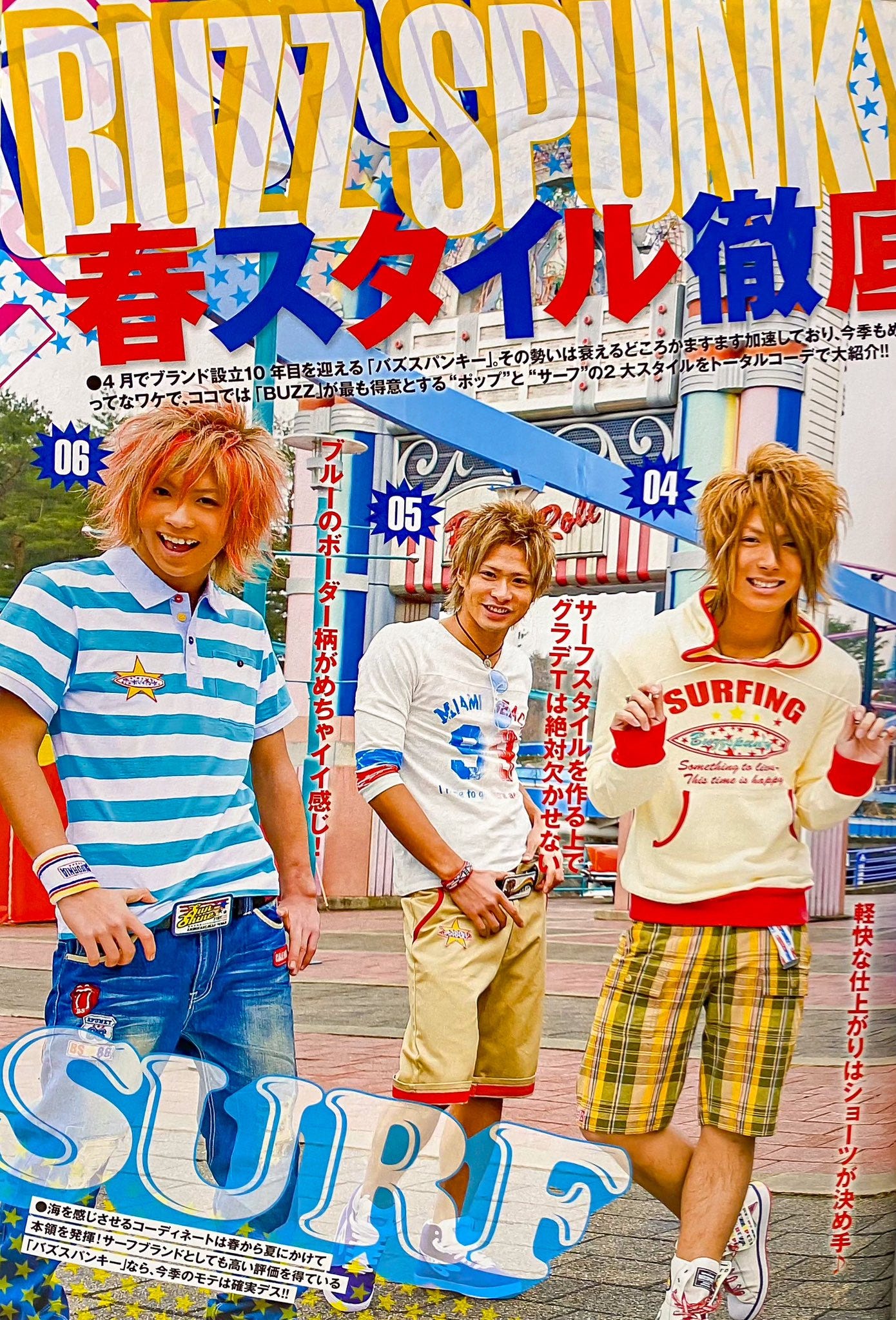

Before the K-pop trend, Japan wasn't heavily influenced by other countries, and it was creating its own unique culture. This gave rise to unique subcultures like "Gyaru" and "Gyaru-o." Television and magazines also still had a strong influence during this time.

To be scouted as a magazine model on the streets of Shibuya, you had to stand out in your own way on the streets. Therefore, Gyaru makeup and fashion became more and more flashy and extreme to catch the attention of magazine photo crews.

Then, the male Gyaru-o also became more and more flamboyant to match their Gyaru counterparts.

Now that magazines are no longer influential, there is less and less point in wearing flashy Gyaru makeup, and the Gyaru and Gyaru-o population has declined in Japan.

How old were you in the 1990s and early 2000s? Do you remember or have direct experience with Heisei trends such as Gyaru or Gyaru-o?

I was born in 1995. I had Gyaru friends at the same school I went to. I also dabbled a bit in Gyaru-o fashion myself.

What were the big trends and popular items that were popular among young people in Shibuya and Harajuku during the Heisei era?

The Heisei era was quite long, so it’s hard to say. There were so many trends. But for example, if you're referring to only around 2010:

In Harajuku around 2010, some trends included “sarouel pants” and "eye-ball accessories."

In Shibuya, among girls, there was a trend of floral skirts and shirts, dungaree shirts, and hippie headbands inspired by singer Nishino Kana.

Among boys, loop ties were a popular fashion accessory during this period.

Recently, I’ve seen that several major companies in Japan, such as McDonald’s, (beef bowl chain) Matsuya, and even Pizza Hut have done Heisei style ad campaigns. Is it fair to say that there is a larger Heisei Boom happening now in Japan?

It seems like these advertisements are more of an attempt to ride the wave of the Heisei Retro trend rather than a sign of a significant Heisei Boom. The advertisements for McDonald's and other brands with a Heisei theme don’t seem to have a high production quality and aren’t very well done. I think that they are simply "taking advantage of the Heisei Retro trend".

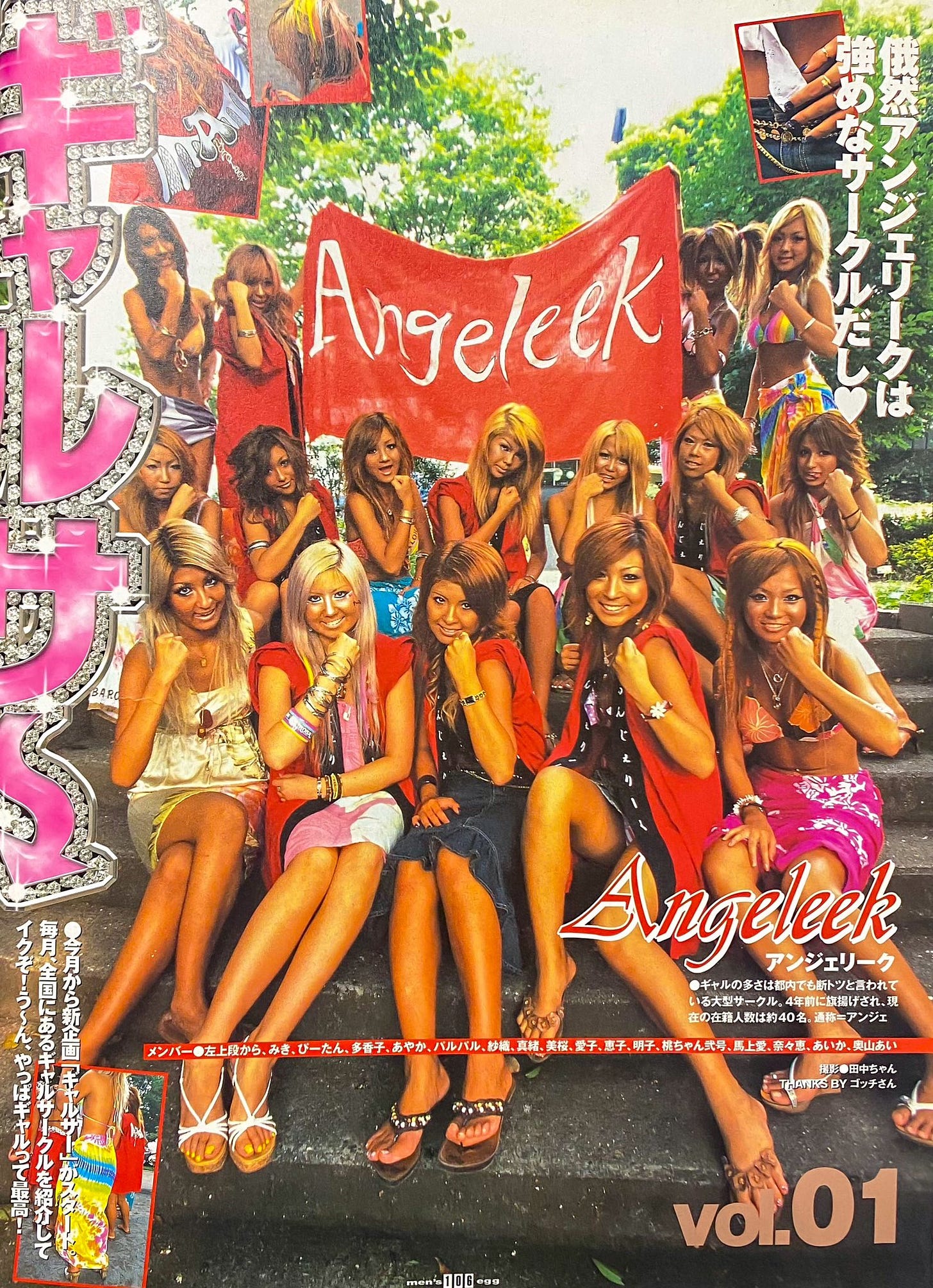

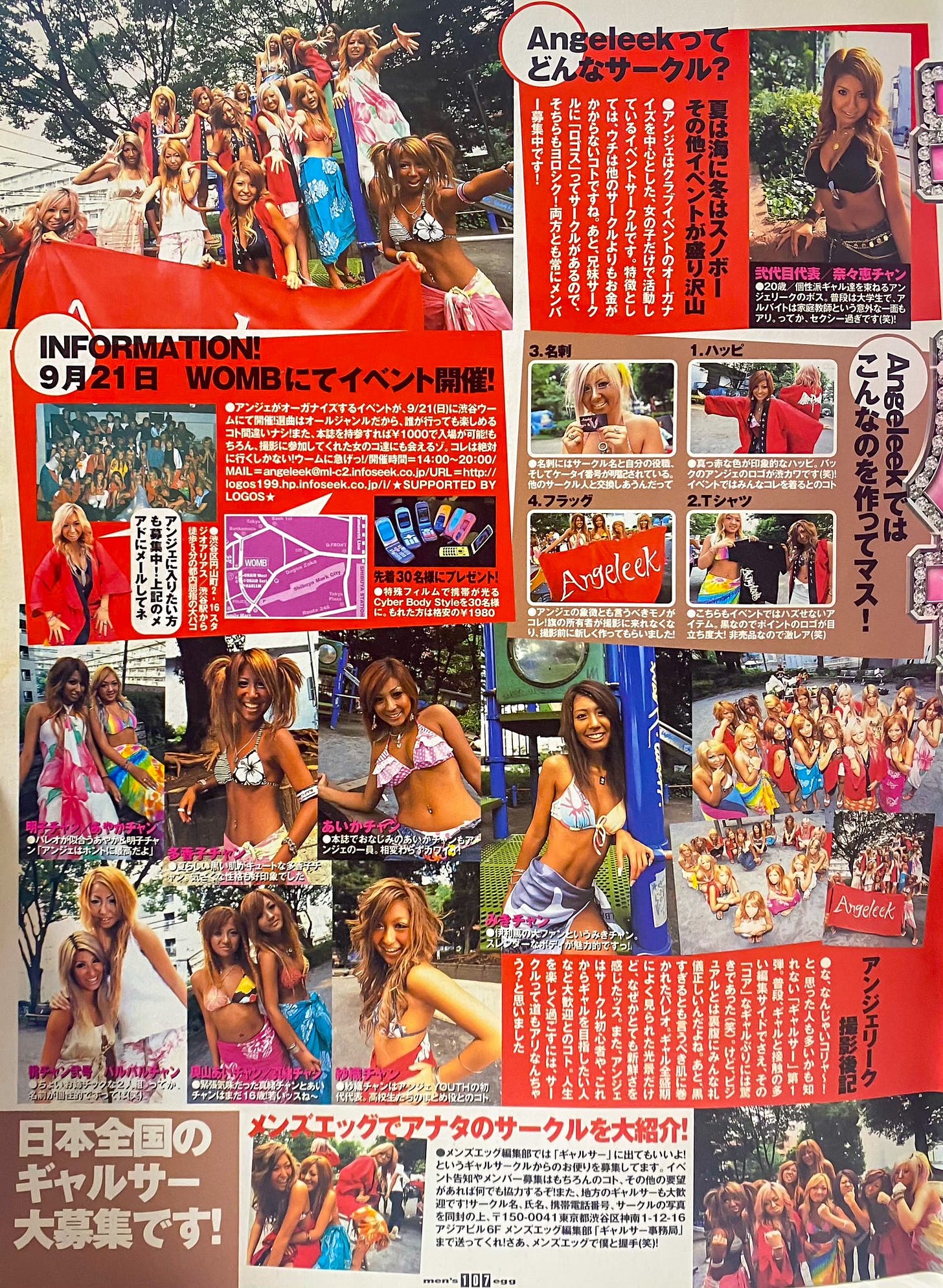

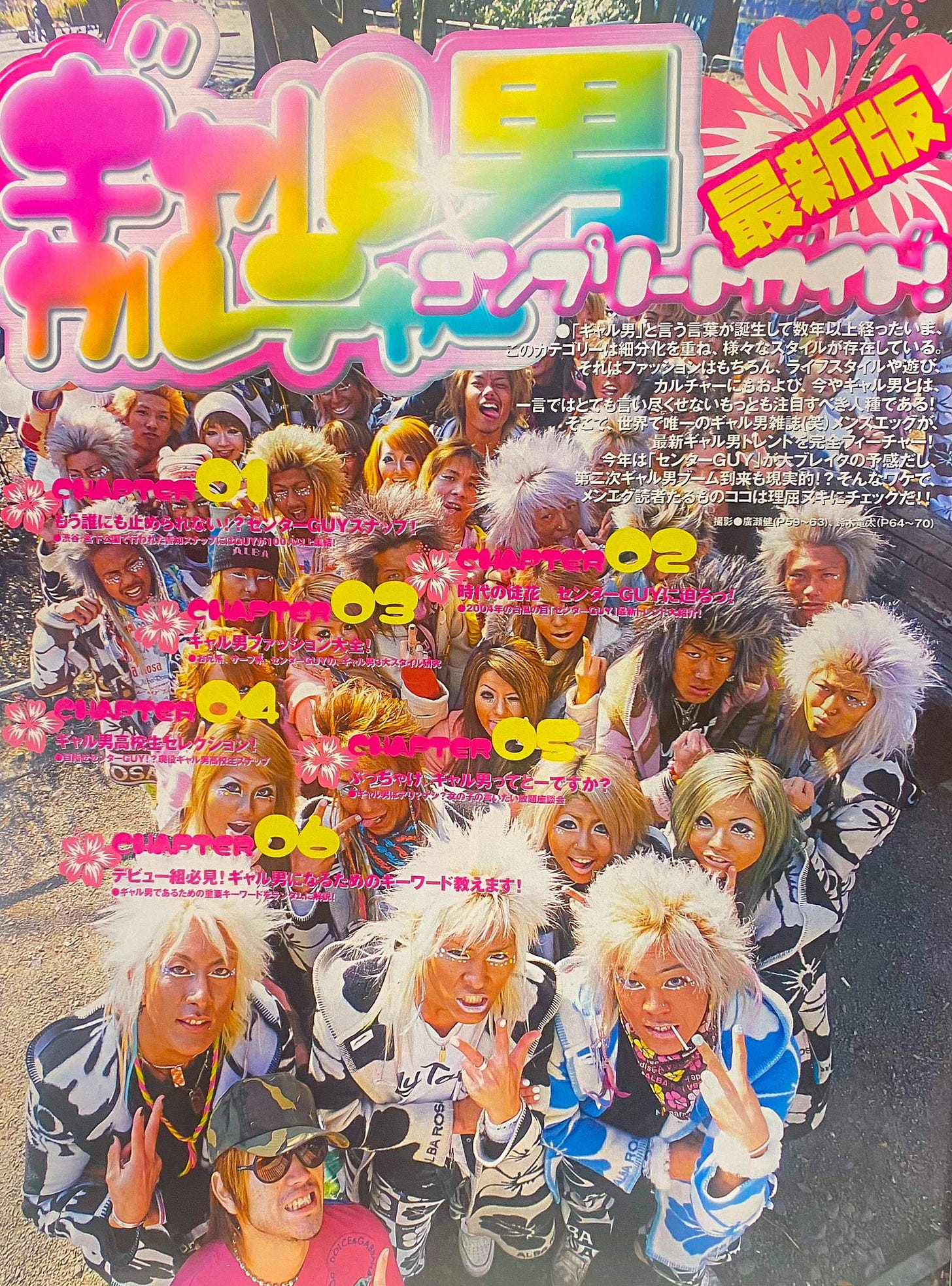

I started following Japanese subculture fashion starting in the early 2000s and I was struck not only by the clothing and style, but also by magazines like egg and Men’s egg. How would you describe them?

Basically, egg is a fashion magazine for gyaru women, and men's egg is the male version of the magazine for gyaru-o.

Do you remember the first time you saw a magazine like egg or men's egg? How did you feel? How do you feel when you look at these magazines now?

I don't remember it well. Even without seeing it in magazines, there were plenty of gyaru and gyaru-o in my neighborhood, so it wasn't that shocking, just normal.

I still revisit some back issues from time to time, but magazines like egg and men's egg aren't as flashy as people might think; they're quite casual.

I believe that Ranzuki and Men's Egg Youth, which were more targeted at teenagers, and have more pages with the vibrant and powerful colors and styles that were unique to that time.

A lot of the articles in these magazines were about sex: how-to pick-up girls (nampa) and even techniques in bed. I don’t really see this kind of stuff in Japanese media anymore. How have attitudes about sex and gender changed since the Heisei era?

I don't think the thinking has changed much, but it is a mystery whether articles on pick-up and bed techniques were actually in demand even then. I myself read those magazines, but I was only interested in the fashion pages and skipped the nightlife and pick-up articles without reading them.

Today, many young people are negative about sexual activity itself, let alone picking up women, and I think it is easier for women to speak out against being sexually exploited by men.

Another thing that strikes me about this time: the kids in the street snaps in these magazines look like they are having FUN. When I see pictures of street fashion now on the internet, I think people are now trying to look cool (not smiling, etc.). What has changed about street snaps?

I think it's the difference between snapping a group of people having a good time and snapping a fashionable, pretentious person.

When I look at magazines like egg and men’s egg now, I wonder, what happened to all the gyaru and gyaur-o? Did they become office workers? Did they get married and have kids? What do you think happened to these people 20 years later?

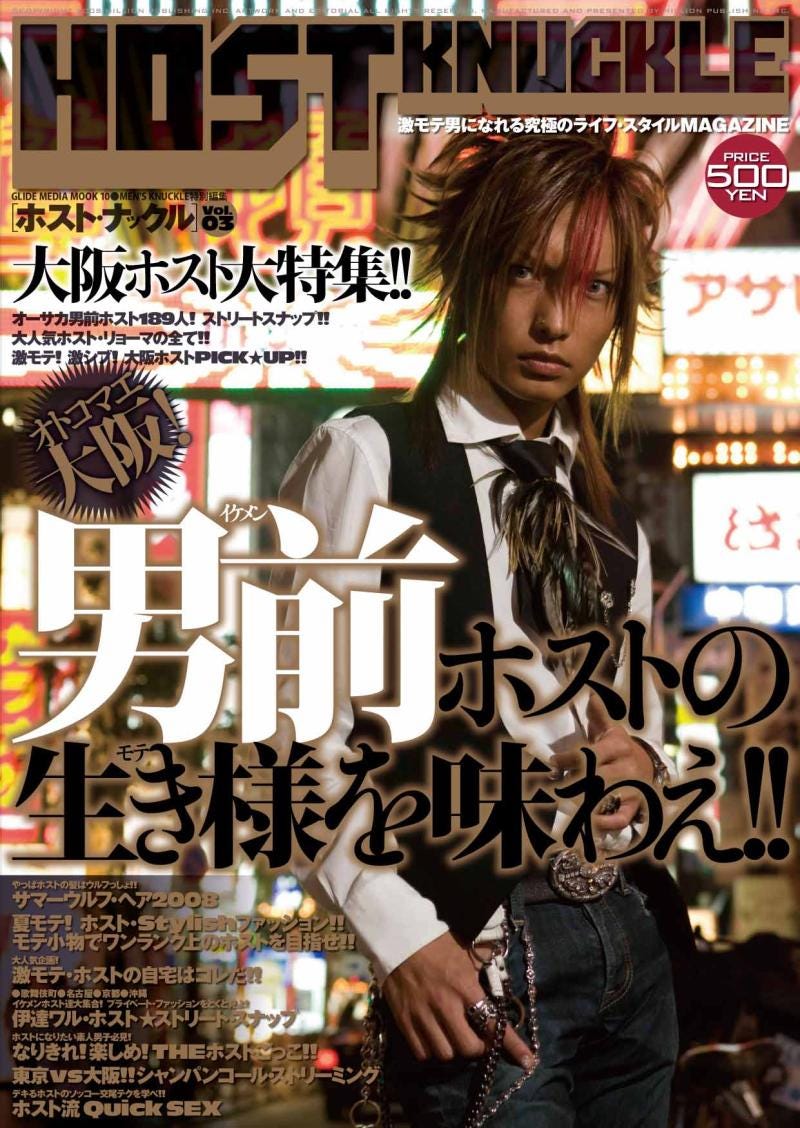

The most common second careers for gyaru and gyaru-o were in cabaret clubs and their management: beauty, etc. for women and host clubs, bar management, apparel, etc. for men.

Some now have families and some are single, but it is often difficult to find out what the former gyaru and gyaru-o models are up to on social networking sites.

Gyaru-o seems like it was closely connected to the host club industry, even more than gyaru was connected to the hostess industry. Why did gyaru-o seem to go away, but host clubs still remain popular?

Hosts have transformed their appearance from the older gyaru-o style and have now adopted a more 'menchika' (underground male idols) or 'K-pop style' look, so their visual style is completely different from what they used to be. Hosts always adapt to the current trends of the time, so in the present day, there is little connection between gyaru-o guys and hosts.

I’m curious how you think the internet has impacted Japanese fashion and youth subcultures. Certainly, magazines like egg and men’s egg had trouble staying in business as people abandoned print for the Internet, but how else have things changed?

I think fashion has become more diverse than ever before because of the Internet. It has changed the way we look at fashion from the days when we relied on magazines and took a few popular models as role models. Now there are a variety of influencers who are popular and there are a variety of role models to follow.

If someone wanted to style themselves as a gyaru-o or men’s egg model from this era, what are some essential items they should have?

Silver accessories, leopard print fabric, bracelets, V-neck or draped neck shirts, distressed jeans, pointed-toe shoes, wallet chains, and hair wax for styling.

I know you recently did a collaboration with GLOOMY BEAR, who first debuted during the Heisei era. Are there any other original characters or goods from that time that you think should make a comeback?

I would like to see the return of old San-X characters such as “Amaguri-chan” and “Mikan Bouya.”

How do you think Shibuya and Harajuku have changed for young people since the Heisei era? What is your impression of these places now?

I don't think Harajuku and Shibuya are as influential now as they used to be. This is because each town has lost its "unique character" that existed in the Heisei era. Now every town is no different from the others.

There are no iconic figures representing these neighborhoods, so I believe that nurturing such individuals is the current challenge.

Who are some of your favorite singers or groups from the 1990s to the Heisei era?

The Brilliant Green, Do As Infinity, Hitomi Takahashi, Nishino Kana, YUI, Folder 5, and mini.

What are some of your favorite clothing brands from the Heisei era?

Finally, do you have a message for any readers around the world about Japan and the Heisei era?

I believe that the gyaru and gyaru-o subcultures are quite rare in the world, and many people who are not familiar with Japan's past still don't understand what they are.

In Japan, the gyaru culture is even more deeply rooted than the Harajuku KAWAII culture. On the other hand, abroad, it seems that the Harajuku KAWAII culture is more well-known, and the awareness of Japan's gyaru culture is relatively low, which creates a sense of wonder and a gap between Japan and other countries.

Both of these cultures are symbolic of Japan, so I hope there will be more opportunities for people to get to know them.