How Japan’s Wild Yamanba Gal Culture Is Being Preserved in Art History

Japanese pop culture news edited by Patrick Macias

Yamanba’s extreme makeup and fashion style were once a powerful social phenomenon in Japan

Artist Tomomi Kondo, a former Yamanba herself, is archiving the movement for future generations

Kondo now reinterprets Yamanba alongside avant-garde art movements in her work

A Shibuya Movement That Shaped Youth Culture

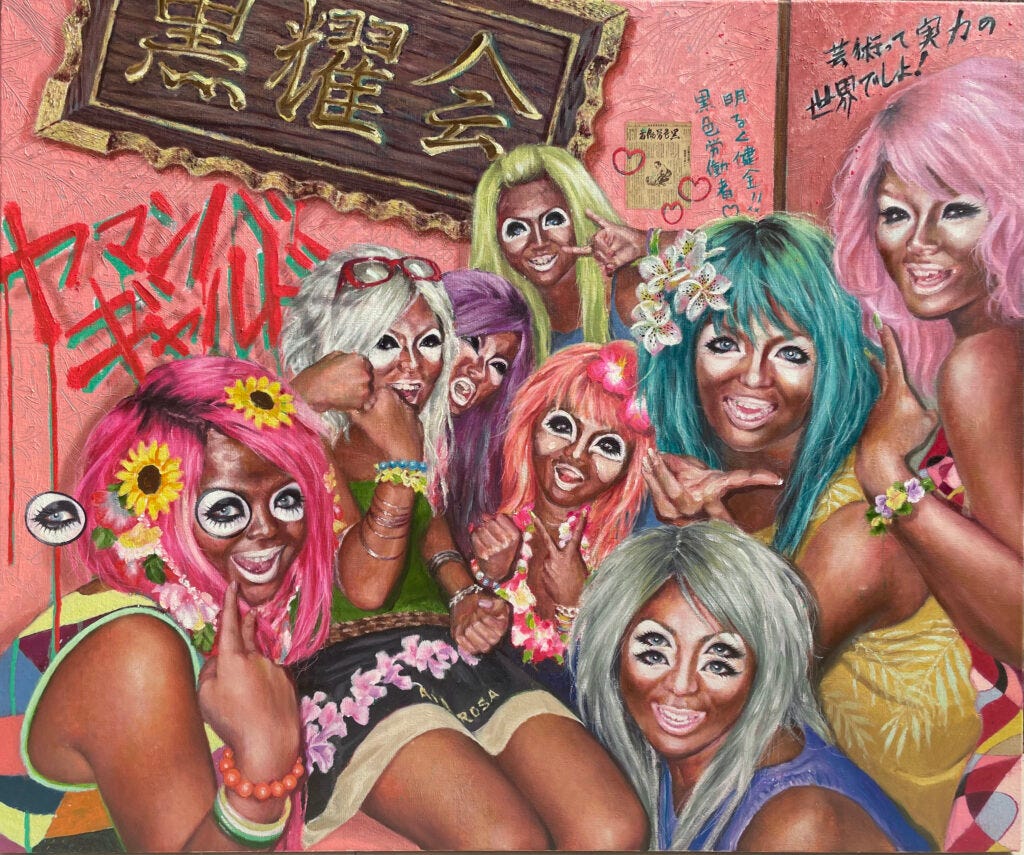

Between 1999 and 2004, a style known as “Yamanba” appeared in Shibuya, Tokyo. Its defining traits were deeply tanned skin, and brightly colored hair. The movement spread rapidly, drew media attention, and became a social phenomenon.

This interview was conducted with artist Tomomi Kondo, herself once a Yamanba, who is now committed to documenting the movement and archiving its history. Through her art practice, she seeks to position Yamanba within the framework of Japanese art history.

Pushing Style to the Extreme

Reflecting on the height of the movement, Kondo explained that originality was everything. “Every day felt like going into a serious competition on Shibuya’s Center Street. Outsiders might have thought we looked the same, but each of us was determined to avoid duplication,” she said. “We did not aim for grotesque forms. They emerged naturally from experimenting with makeup. For us, to push things to the extreme was the same as being beautiful.”

Kondo emphasized that their style was based on constant exploration. “We were always searching for new, stimulating motifs. clothing from other countries, masks, and cosmetics inspired us. Our understanding was shallow at the time, but the sense of style was extraordinary,” she noted.

An Expression Close to Contemporary Art?

Although the media portrayed gals as carefree, Kondo recalled a different reality. “Romance and media attention had nothing to do with it. We only cared about challenging ourselves with something new,” she said. Looking back, she sees the movement as an art form. “It was very close to contemporary art and performance. Pushing the limits clarified our sense of beauty, similar to Japan’s traditional arts that emphasize lifelong training.”

Kondo grew up in Hiroshima in an academic household, with parents who were professors and siblings who pursued scholarly paths. “I was the odd one out. I liked drawing and adopted some gal fashion, but I was not fully into it yet. My high school was strict, and I grew rebellious. Teachers claimed they disciplined us for our sake, but it was really about appearances. That made me more defiant,” she recalled. She explained that by the early 2000s she was determined to go to Shibuya. “I belonged to the second generation of the style called Manba. I decided I would go to Shibuya after graduation no matter what. My parents allowed it if I enrolled in a vocational school, so that is how I moved to Tokyo.”

Accepted Into the Yamanba Circle

Remembering her first steps in Shibuya’s Center Street, Kondo said, “I was nervous but had seen Yamanba in magazines. I decorated my hair with a big hibiscus and sat on the roadside. A Yamanba passing by asked where I bought it. I said, ‘At the 100 yen shop. It is a bathroom decoration.’ They replied, ‘This girl has potential,’ and let me in their tribe.” She added that not everyone was welcomed. “It seems those with sharp instincts, rebellious spirit, or some kind of edge were recognized.”

Decline of Yamanba and Rise of the Internet

Kondo explained why the movement declined around 2004. “Some began chasing media exposure, which diluted the purity of the activity. At the same time, the internet grew. Before, we expressed ourselves through tans and makeup. Once recognition came through phones and smartphones, the need to invest so much energy into appearance diminished.”

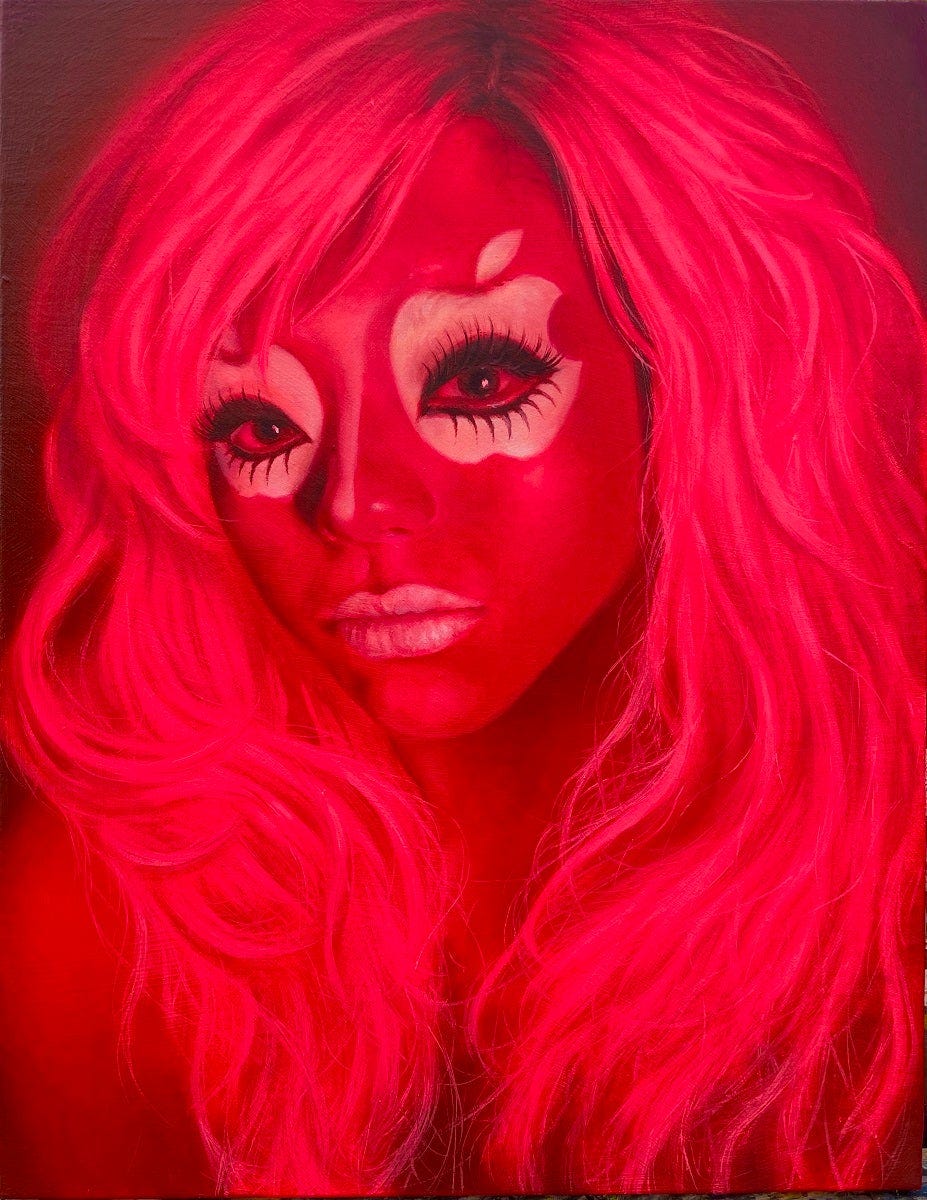

With time, Kondo began reexamining Yamanba through her work. “With distance, I could see it more objectively. I began using Yamanba motifs in my art, thinking of it as part of art history. I created series linking it to movements like Futurism, Cubism, and Neue Sachlichkeit, which influenced avant-garde art in early 20th century Japan,” she explained.

Parallels With Avant-Garde Expression

She also discovered parallels with Japanese avant-garde groups. “Yamanba had no leader or doctrine, so calling it a movement is tricky. But when I studied the Taisho-era avant-garde, I saw similarities. They formed movements through urban culture and magazines, with groups forming and dissolving repeatedly. It was very close to what we experienced,” she said. Research trips in 2024 further shaped her views. “In Berlin, I saw how the golden age of 1920s German painting and Neue Sachlichkeit still echo in contemporary art. It convinced me that Yamanba could still function as visual communication today.”

Passing Down a Legacy for Future Generations

For Kondo, preservation is now essential. “Because Yamanba disappeared before the internet age and never spoke for itself, its reality has become a black box. Yet the drive for expression it embodied is something we can learn from. I fear that talking about it may ruin its beauty, but as someone inside it, I want to record it objectively before it becomes romanticized. Preservation is for the future as much as the present. By recording it properly, I hope Yamanba will one day be reinterpreted creatively and recognized within art history.”

Upcoming Talk at the Yayoi Museum

Tomomi Kondo will appear at a gallery talk with scholar Yuka Kubo, author of The Last Days of the Ganguro Tribe.

Date: Saturday, August 23, 2025, 3:00 PM (approx. 40 minutes)

Venue: Yayoi Museum, 1st Floor (Bunkyo, Tokyo)

Admission: Free with museum entry, no reservation required

For details, visit the Yayoi Museum website.

![元ヤマンバの画家、近藤智美さん [写真特集1/8] | 毎日新聞 元ヤマンバの画家、近藤智美さん [写真特集1/8] | 毎日新聞](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!OH3V!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Febbb54f7-eca8-41d5-a990-dd25a5443d81_800x533.jpeg)

My faves were the 汚ギャル

Fascinating how an artist has come out of this trend.

I shot Japanese street fashion between 2002 and 2015, and published the first English language fashion blog about Japanese street fashion, JAPANESE STREETS. I can't recall, but I don't think I took any photographs of Yamanba. It was just too far removed from what I was shooting at the time, which was more focused on Amemura in Osaka, and Tokyo's Harajuku district.

I like how Tomomi Kondo now interprets the trend as an art movement. Looking forward to how she will further develop this.

Thanks for sharing, Patrick.