Analyst Says McDonald’s Japan Was Totally Unprepared for Pokémon Resale Chaos

Japanese pop culture news edited by Patrick Macias

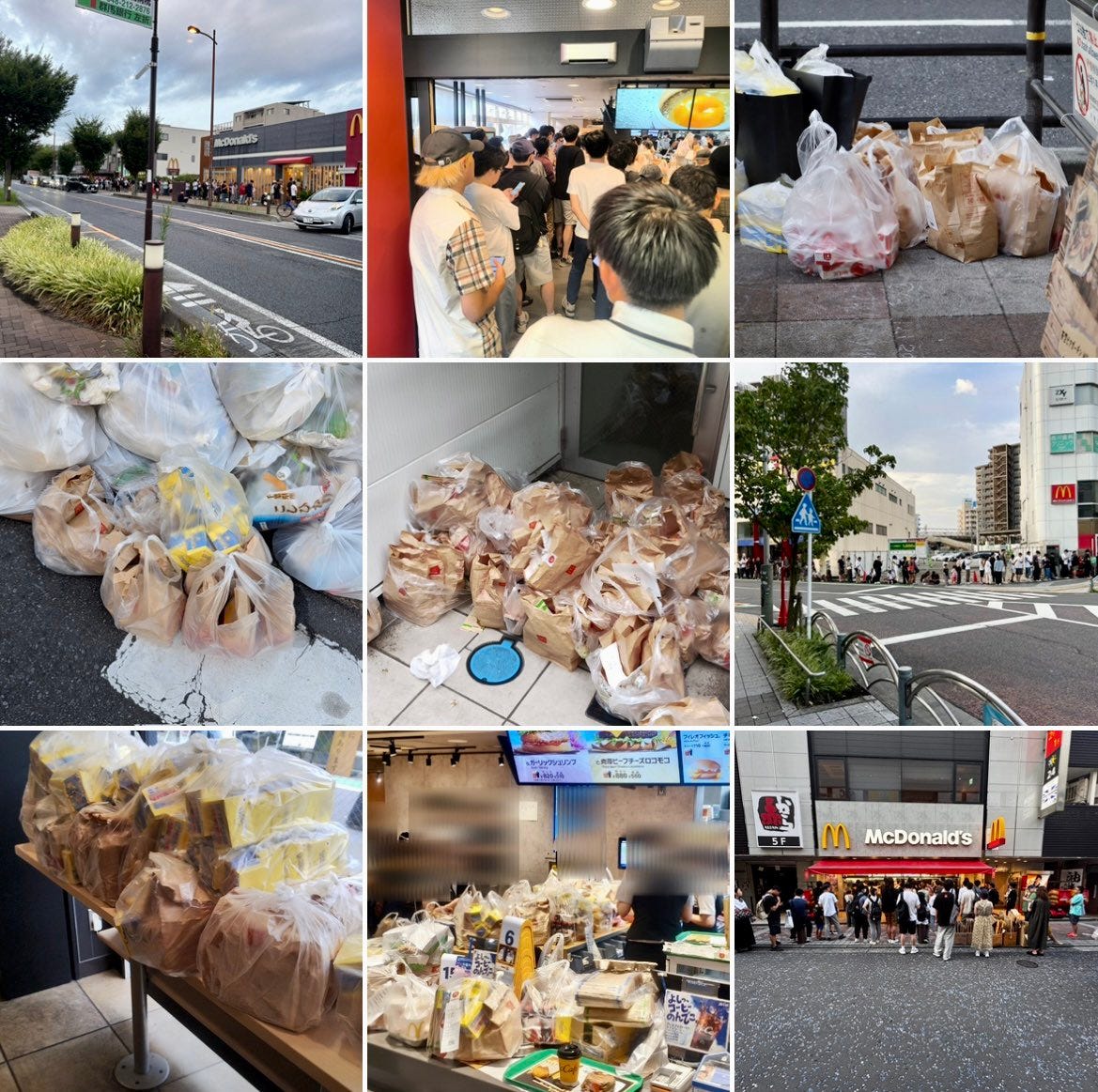

Limited run Pokémon Happy Meals sold out within hours due to organized reseller activity, leaving genuine customers empty handed

McDonald’s faced criticism for failing to align its food waste reduction message with promotion mechanics that encouraged waste

Business analyst Takayuki Sakaguchi says proactive anti resale measures are now essential for brand credibility and customer trust

From August 9 to 11, 2025, McDonald’s Japan launched a limited run Happy Meal featuring collectible Pokémon cards. By the morning of the first day, the product had already disappeared from stores across the country. The sellout was not driven by loyal customers but by organized reseller activity, a predictable market behavior that the company failed to contain.

What began as criticism of resellers quickly shifted toward McDonald’s itself. The brand’s inability to protect its promotion from exploitation has become a discussion point in Japan about modern corporate responsibility, stakeholder impact, and the business costs of operational oversight failures.

Reseller Limits That Fell Apart Faster Than a Soggy Bun

McDonald’s partnered with the flea market platform Mercari to limit resales, set a five set per customer rule, and appealed to customers’ “good conscience” not to order more food than they could consume, according to the company’s initial announcement. Even so, resales proliferated online and food waste became a visible outcome.

In Japan, continuous profit driven reselling requires a secondhand dealer license, though reselling itself is not outright illegal. Critics argued that a company publicly promoting “community coexistence” and “reducing food waste,” as McDonald’s has done in previous campaigns, had created conditions that incentivized throwing food away. As one consumer complaint put it online, “They failed to meet the needs of genuine fans, and instead attracted complaints.”

A Press Release That Tried to Put Out a Grease Fire

On August 11, McDonald’s issued a public statement outlining tighter purchase limits, new restrictions on mobile ordering, and the right to refuse sales to aggressive customers. This prompt release showed responsiveness to public sentiment, but the underlying economic incentives remained unchanged.

Explaining why food disposal became common among resellers, business analyst Takayuki Sakaguchi wrote, “If something worth 10,000 yen is being sold for 1 yen, then hiring people to wait in line and discarding the food is the quickest route to profit. Of course, anyone with a conscience would not do this. But those lacking ethics will behave rationally in this way, and they did.”

Social Media Turned into the World’s Loudest Complaint Desk

Once the resale activity became visible, social media platforms were flooded with posts from customers. Common messages included, “Children could not buy one,” “Only foreign resellers profited,” and “Staff looked the other way.”

In its August 11 apology, McDonald’s Japan acknowledged “food waste, abandoned meals, and confusion in stores” and addressed the apology not only to customers but also to “store crew, nearby residents, and tenant landlords.” The company confirmed that these groups had been directly affected by the disruption.

When Following the Law Just Does Not Cut It Anymore

The incident reflects a shift in market expectations. According to Sakaguchi, “Consumers today are quick to sense hypocrisy, a gap between what companies say and what they actually do.”

Allowing resellers to block loyal buyers undermined McDonald’s stated commitment to sell “to the customers who truly want the product.” The gap between message and execution represented a failure of brand governance rather than a legal lapse.

Crew Members Did Not Sign Up for Fight Club

The second responsibility was to employees. Sakaguchi pointed out that “companies must provide a safe, professional environment as a baseline for sustaining operations.” Yet videos on social media showed “customers shouting abuse, lodging complaints, and taking an intimidating stance,” with even physical fights breaking out between customers.

While Sakaguchi did not claim that McDonald’s had committed direct labor law violations he emphasized that such incidents “impose excessive physical and mental stress on staff” and can have a negative impact on retention and recruitment.

The third responsibility extended to the local business ecosystem. Sakaguchi noted that “neighboring tenants were inconvenienced, in some cases incurring waste disposal costs and lost time.” He argued that failing to anticipate these impacts created operational and financial burdens for partners.

The Plot Twist Where McDonald’s Became the Villain

Initially, public anger targeted resellers. Sakaguchi observed, “The tone shifted rapidly toward criticism of McDonald’s.” The company’s August 9 statement contained no specific improvement measures, which reminded customers of the “Chiikawa Happy Meal” incident of May 2025, when similar crowding and resales had occurred.

During the same period, Nintendo launched the Switch 2 with a targeted sales strategy favoring existing paid members. While this did not eliminate resellers entirely, Sakaguchi noted that “the number of resellers was small.” Many consumers compared the two cases and concluded that McDonald’s had not taken the resale risk seriously.

Prevention Efforts That Looked Good Only on Paper

Some customers stated online that McDonald’s “was not serious about pre-event prevention.” Others felt the company was “promoting food waste reduction while prioritizing profit.” Sakaguchi added that some critics “even questioned internal decision making, suggesting the company had placed short term revenue above long term brand value.”

While executives might claim that resale activity is beyond corporate control, Sakaguchi countered that “the company’s own marketing promise and the financial value of maintaining it make proactive prevention a business necessity.”

The Public Now Expects More Than Just Fries with That

For high demand items, consumers expect companies to take “every possible measure” to ensure fair access. Sakaguchi stressed that “the expectation is not for the impossible, but for visible, proactive effort.” Failure to act invites reputational harm and customer distrust.

Sakaguchi also commented on the social environment: “We live in a society where feelings of being disadvantaged are strong, and resentment grows toward unfair people profiting from characters and the companies that encourage them.” This dynamic explains why the Happy Meal promotion became more than a minor operational misstep.

From Complaints to Creative Fixes

Looking ahead, Sakaguchi proposed that “if anyone has a clever, low cost, feasible way to prevent reselling, they should actively propose it to companies.”

He concluded that “if workable, such proposals will be considered, aligning the promotional goal of bringing smiles to children with operational practices that protect both customer trust and brand value.”

Food waste is horrible and the people who did that have low morals, and yet, they do have some morals it seems since even though they threw out a large amount of food and tossed it in weird places as seen in the pictures, they still kept all the unwanted food in a giant trash bag! So Japan!

Why not eat the food or give it out to people?